Natural heritage

THE HEARTS OF BIODIVERSITY

THE HEARTS OF BIODIVERSITY

The region of the communauté de communes offers a rich and varied biodiversity. Certain areas of the region are designated protected or inventory zones.

Natura 2000 Zones

The Natura 2000 network is a collection of European natural sites, both land-based and marine, that have been identified for the rarity or fragility of their wild species, whether plant or animal, and their habitats. The measures taken by Natura 2000 reconcile the preservation of nature with socio-economic concerns.

There are two Natura 2000 zones in the region of the communauté de communes, both the subject of a number of recommendations as part of their respective documents of objectives:

- La zone Natura 2000 du massif du Bargy, concerning the communes of Marnaz, Mont-Saxonnex, Le Reposoir and Scionzier.

- La zone Natura 2000 du massif des Aravis, concerning the communes of Magland, Nancy-sur-Cluses and Le Reposoir.

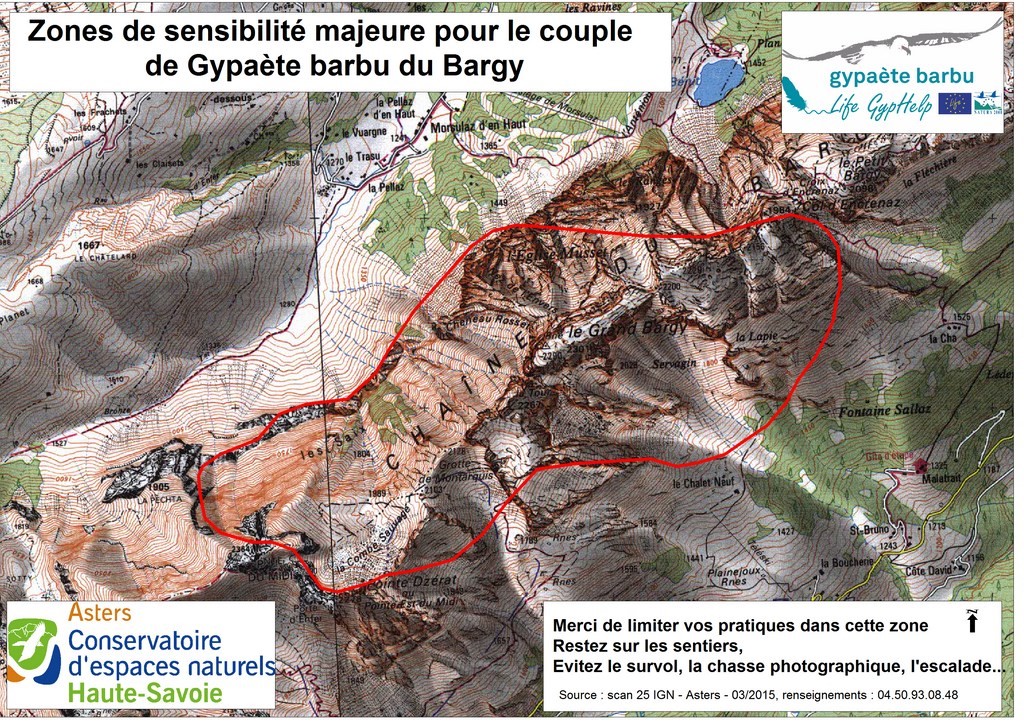

The Bergy and Aravis ranges are listed as special protection zones according to the Birds Directive, and as a site of community importance according to the Habitats Directive. In particular, these massifs shelter couples of the bearded vulture, a protected and emblematic species of the Alps.

Nature-based activities are possible in Natura 2000 zones, but the areas and periods of sensitivity of the notable species must be taken into consideration in order to best reconcile human activity with the preservation of biodiversity.

Site d’Arrêté Préfectoral de Protection de Biotope

An Arrêté Préfectoral de Protection de Biotope (APPB) is an apparatus applied to a defined space that uses specific regulatory measures in the aim of preventing the disappearance of protected species.

The territory of the communauté de communes includes an APPB listed area: the peak of Chevran mountain, at the level of the rock and forest areas located in the communes of Arâches-la-Frasse and Cluses. These areas shelter remarkable and protected birds. The peregrine falcon, the wallcreeper, the black woodpecker… Inside this zone, certain measures apply, such as a ban on the practice of rock-climbing and free-flying less than 200 metres from the rock face between 15 February and 30 June.

Available for download: APPB du Chevran

Site naturel classé

A site classé is an area whose historic, artistic, scientific, legendary or aesthetic character demands – in the name of general interest – preservation and protection from any major damage.

Lac Bénit, located in the communes of Marnaz and Mont-Saxonnex, has been a site naturel classé since 1906.

Sites classés are subject to certain systematic instructions and bans: advertising and camping are forbidden.

Zones Naturelles d’Intérêts Écologique, Faunistique et Floristique

The inventory of Zones Naturelles d’Intérêts Écologique, Faunistique et Floristique (ZNIEFF) aims to identify and describe well-preserved areas with strong biological capacities. There are two kinds of ZNIEFF:

- ZNIEFF Type I: zones of major biological and ecological interest.

- ZNIEFF Type II: more extensive nature blocks, rich and largely untouched, offering high biological possibilities.

The territory of the communauté de communes includes several ZNIEFF Type I:

- Mont d’Orchez – Pic de l’Aigle

- Versant rocheux en rive droite de l’Arve, de Balme à la Tête Louis Philippe

- Rives de l’Arve, d’Anterne aux Valignons

- Combes de Sales

- Tête du Coloney – Désert de Platé

- Rochers de Leschaux, plateau de Cenise, Andey et Gorges du Bronze

- Rochers de Leschaux, plateau de Cenise, Andey et Gorges du Bronze

- Chaîne des Aravis

The region of the communauté de communes includes several ZNIEFF Type II:

THE BEARDED VULTURE, A HISTORY OF ITS REINTRODUCTION

A species symbolic of the Alps, the bearded vulture had nonetheless entirely disappeared from the region. Following several programmes of reintroduction, however, the bearded vulture can once again be found in the Alps, but it remains one of the most endangered species in Europe. On French soil, it is the subject of a national plan of action that aims to define the measures necessary for its restoration and conservation.

An Exceptional Species: Characteristics, Disappearance and Protection

The bearded vulture belongs to the species of vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), ‘from the Greek Gyps, the vulture, and Aetos, the eagle; its appearance is very close to that of the golden eagle, but it is fundamentally distinguished by its vulture’s diet (Rouillon, 2002: 127)’.

Indeed, it feeds essentially on bones, supplemented with animal carcasses, and its settlement areas are directly linked to the presence of wild or domesticated ungulates. It plays an important ecological role in eliminating corpses, preventing epidemics and parasites, and protecting waterways from pollution resulting from decomposition. When the bones are larger than 30 cm, the bird releases them from a height onto a rock in order to break them.

The bearded vulture has a wingspan of up to 3 metres and its life expectancy is around thirty years. But ‘their sexual maturity comes late (at 7 years) and their rate of reproduction is weak (less than one offspring per year) (Coton & Estève, 1990: 227)’.

The bird could be found ‘until 1850 […] from lake Léman in the north-east to present-day Slovenia in the east and the Mediterranean in the south (Rouillon, 2002: 127)’ before it was exterminated up until the 1920s. The domestication of the mountain environment and the resulting drop in number of wild ungulates favoured the disappearance of this bird of prey from the Alps, but the direct intervention of Man was the major cause. As with the wolf and the bear, the bearded vulture was violently discriminated against by the mountain residents, who saw in it ‘the silhouette of a terrifying beast attacking flocks and children […] firearms, as well as poisons, got the better of it (Coton & Estève, 1990: 227)’.

Listed as a “Protected Species” in France since the ministerial decree of 17 April 1981, the species is also listed, on the European level, in Appendix I of the Birds Directive n°79/409/CEE of the Council of Europe of 2 April 1979. It is also listed in Appendix II of the Bern Convention of 19 September 1979, in the Bonn Convention of 23 June 1979, and in the Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) of 3 March 1973 (Haute-Savoie Conservatory of Natural Spaces).

“THE BEARDED VULTURE OR OSSIFRAGE. An animal gifted with great strength but without pride or courage. It is a formidable bane for the flocks. Man himself is not safe from its voracity”

Source: Haute-Savoie archives, drawing from the Imprimerie Noel, Paris, undated.

The Programme of Reintroduction: A Human and Animal Odyssey

From the early 20th century, the question of the reintroduction of the bearded vulture was being posed. Protecting nature had become a civic duty and ‘rebuilding the heritage that we have amputated (Michelot 1991)‘ a mission for nature lovers and ecologists. On 15 June 1973, the first transnational assembly for the reintroduction of the bird of prey to the Alps took place. It was then undertaken to capture birds in Afghanistan so as to hold them in captivity in Haute-Savoie. The aim was to form reproductive couples to produce offspring that could then be introduced into the natural environment.

A total of eleven birds were imported, but in the course of several unexpected incidents, 4 died, 3 were freed and 4 would go on to form reproductive couples in a later project (Coton, Estève, 1990: 228). In 1978, in Switzerland, it was decided to merge together the entirety of reintroduction projects in the Alps into one single programme of conservation.

‘Faced with the low potential of wild animals and a widespread decline in populations, it was decided that only birds held in captivity in the various European zoos were to be used. Only those animals born from captive couples would be released (Ibid. : 229). ‘

Ten years later, after a long period of evaluations and proposals, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) selected a method of reintroduction without an acclimatisation aviary, prioritising the flight of the birds.

‘The young three months of age, that is, capable of feeding themselves alone, were placed on a cliff especially equipped to receive them in the natural environment. During the final month before leaving the nest, they were subject to permanent surveillance, and the provision of food was carried out in the evenings so that they would not become steeped in human presence (Rouillon, 2002: 127). ‘

It was at this time, following an evaluation, that it was decided that the first French birds should be released in the valley of Le Reposoir in Haute-Savoie, in 1987. After a comparative study, this area had revealed itself to be the most appropriate site for settling the bearded vultures. It consisted of 62% non-forest terrain, a climate favourable to nesting and a population of over 3000 domestic goats with a high mortality rate in summer (Coton, Estève, 1990: 231).

Based on the previous failure, in Austria, of monitoring the birds with telemetry, it was undertaken to bleach ‘a few feathers with hydrogen peroxide’ and to deploy ‘a vast network of voluntary observers’ in Le Reposoir (Rouillon, 2002: 129). Unfortunately, out of the three birds released, two died as the result of accidents.

On 28 May 1988, a new settlement of young bearded vultures was carried out, and as Mauz highlights, the reintroducers had a ‘pioneering spirit’ and ‘had to manage everything, find solutions at short notice, and demonstrate determination and audacity (2006: 6)’.

This time, the bearded vultures seemed to have found their place, which ‘confirmed for the Métral family, the Alpine farmers hosting the reintroduction programme on their mountain, that the site offered tranquillity and abundant nutritional resources (Rouillon, 2002: 129)’. The lands of this family had been selected for their qualities as ecosystems, and the Métrals themselves approved of the programme of reintroduction (Pierre Métral, personal communication, 11 February 2016). What followed was a series of regular reintroductions, five birds in 1989, two in 1990, 1992 and 1993, as well as the establishment of a new release site in Mercantour National Park. These various reintroductions likewise saw many tragic accidents, but ‘ the year 1997 would finally honour this decade of effort. The couple formed by Melchoir and Assignat gave birth to the long-awaited offspring: Phenix Alp Action, who would leave the nest on 5 August (Ibid. : 130)’.

In Haute-Savoie, 31 birds were reintroduced between 1987 and 2001 (Ibid. : 132) but the ‘central concern of the reintroduction programme was to foster natural reproduction, which must take over from the reintroductions in order to constitute an autonomous population (Ibid. : 131),’ as Rouillon reminds us. This reintroduction had its price. For the French programme orchestrated by the LPO which lasted four years and concerned only the French Alps, some 1.08 million euros were necessary to cover the releases, the conservation and the communication campaign (Ibid. : 133). 1.5 million euros were likewise invested in the transnational programme.

Despite a difficult start, when it had been necessary to understand the bearded vulture, define the method of reintroduction and overcome many failures all at once, this programme of reintroduction appears to have been a success. At present, the species is managing to reproduce autonomously in its natural environment. ‘In the year 2015, 33 reproductive couples were identified across the Alpine arc, of which 9 were in France, 23 offspring were born between February and April, and 20 of them left the nest. It is the first time that so many young have managed to do so (Asters).’ In Le Reposoir an exceptional situation has even been observed: the ‘presence of 4 adults and 2 egg clutches in two regular nests (Asters, public information, February 2016)’ at a close distance, when normally nests are surrounded by a zone of exclusion for both intruders and fellow creatures (Asters).

A symbol of a possible balance between man, nature and often opposing stakeholders (breeders, hunters, tourist professionals, ecologists), the reintroduction of the bearded vulture is of both social and ecological significance. It has offered a better management of the corpses of wild and domestic animals which in turn allows an extensive prevention of illnesses.

The bearded vulture is in fact the only bird whose diet is 70% comprised of bones, thus allowing it to be the final agent in the elimination of carcasses, following vultures and crows. This reintroduction generated a unifying project in which ‘hunters have become strongly involved […] alongside members of the administration, managers of protected areas and naturalists (Mauz, 2006: 8)’.

It generates a certain environmental charm that has become a true local asset, as Rouillon says, ‘the appropriation of the programme of reintroduction by the Alpine population is indicated by the growing use of the image of the bearded vulture in tourist promotion: logos, flyers. Sports clubs, ski schools and paragliding schools are using representations of the species for their respective emblems. The agricultural profession recognises it as a sanitary ally due to its diet, which is being increasingly understood (2002: 133)’. In considering it a complete socio-ecological event, that is, an interweaving of the political, economic, cultural, social, technological and ecological, the example of the bearded vulture could act as a textbook case for others species and regions. Following the example of the work done by the anthropologist Philippe Descola, this case of reintroduction aims to demonstrate that the Western boundary between nature and culture, wild and domestic, is at time tenuous, and that man must increasingly think of himself as a living being within the ecosystem. He must renounce his anthropocentrism to allow ‘a less conflicting coexistence between humans and non-humans, and thus try to halt the devastating effects of our voracity and our lack of concern on a global environment for which we are primarily responsible (Descola, 2005: 276)’.

Montigaud Samuel, 2016, Responsible for the heritage valorisation mission, Cluses Arve et Montagnes Communauté de Communes.

Bibliography:

Coton C. & ESTÈVE R., 1990. ‘La réintroduction du Gypaète barbu dans les Alpes’. In Colloquium on the Réintroductions et renforcements d’espèces animales en France, 6-8 December 1988, Saint-Jean-du-Gard, France. Société nationale de protection de la nature et d’acclimatation de France, Paris.

Descola Philippe, 2015. Par-delà nature et culture. Editions Gallimard.

Mauz Isabelle, 2006. ‘Introductions, réintroductions : des convergences, par-delà les différences’, Natures Sciences Sociétés 2006/Supp.1 (Supplément), p. 3-10.

Michelot J.-L., 1991. ‘Les réintroductions animales en Rhônes-Alpes’. FRAPNA/Rhônes-Alpes Region..

Rouillon Antoine, 2002. ‘Gypaète barbu : un programme européen pour une espèce disparue des Alpes’. In: Revue de géographie alpine, volume 90, n°2, 2002. pp. 127-135.

Websites:

Agir pour la Sauvegarde des Territoires des Espèces Rares ou Sensibles, Conservatoire de la Nature Haut-Savoyarde (ASTERS) : http://www.gypaete-barbu.com

Ligue pour la Protection des Oiseaux (LPO) : http://rapaces.lpo.fr/gypaete-barbu